Delaware’s state House and Senate districts must be redrawn and approved by Nov. 7, but legislative leaders have yet to announce a date to convene a special session to vote on the new district lines.

In August, a broad coalition of community organizations sent an open letter calling on Democratic House and Senate leadership to ensure a fair, transparent, nondiscriminatory, and politically impartial process.

On Thursday, one of the letter’s signatories, Common Cause of Delaware, said in a press release, “One month without any response from state leaders has passed since Common Cause of Delaware and a broad coalition of community organizations sent a letter asking for a fair and transparent redistricting process.”

Common Cause of Delaware is now demanding that state legislators “start communicating with the public about this year’s redistricting cycle.”

“Redistricting will impact our elections for the next decade and the people of Delaware deserve to have a meaningful say in the process,” said Claire Snyder-Hall, director of Common Cause of Delaware. “A completely transparent and public redistricting process will ensure we draw fair maps that benefit our communities, not the politicians. It’s time for state leaders to come forward with details about this year’s redistricting process.”

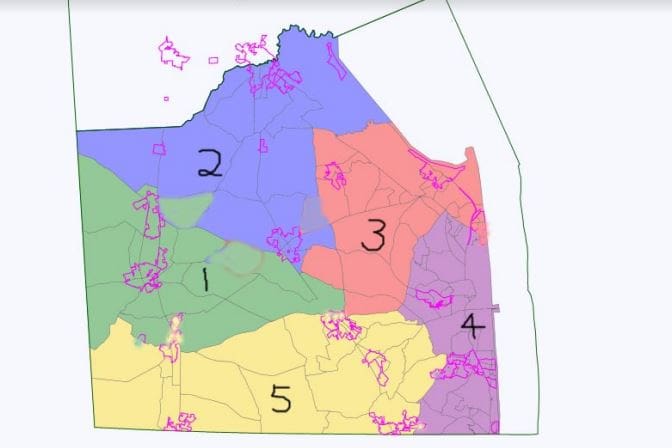

Every 10 years after the federal census is conducted, the legislature is required to redraw voting districts to reflect population changes. Many expect several districts in the northern part of the state to move south as population grows near the beaches and inland.

The district boundaries are adjusted by way of a regular statute and are subject to gubernatorial approval or veto. Districts are required by state law to be contiguous and can not unduly favor any person or party, or disenfranchise groups of voters, including racial and ethnic minority groups.

Common Cause of Delaware said Delaware’s “politicians have the power to draw their own district’s maps, allowing them to determine their voters in elections for the next decade.”

To have that power and not allow adequate time for public input “means there is no check for any politicians who want to draw district lines that split cities or tear neighborhoods apart if it is politically advantageous,” the group said.

The legislature’s deadline for producing the updated district maps was originally June 30, 2021, but six days before that deadline, the General Assembly voted to delay the completion date until Nov. 7, 2021. The deadline was postponed in order to accommodate delays in retrieving accurate census data.

HCR 32, passed on June 23, 2021, said “the final plan or plans to be voted on by the Delaware General Assembly should be a product of a public process.”

In an open letter signed by The League of Women Voters, Common Cause of Delaware, the ACLU of Delaware and 13 others, the groups said they agreed that the citizens of Delaware must have opportunities to provide public comment and see maps.

“We ask that the House and Senate establish dates for open hearings in each of New Castle, Kent and Sussex counties and the city of Wilmington before any maps are created by drafters at the House and Senate levels, and once created are also subject to public hearings on their fairness to all communities of interest within the State before putting into final form,” the letter read.

The groups asked the Democratic leadership to ensure that public hearings are held, at a minimum, 30 days after receipt of the final census data and again 30 days after the maps are proposed by the General Assembly.

State leaders have not shared any information about the current redistricting cycle, including a timeline or how to participate.

Lawmakers thought delaying the process until the fall would provide ample time for accurate census data to become available. However, some say flaws in the data remain as the deadline approaches.

The most recent problem is that the state’s prison population have been designated as residents of the prison in which they are incarcerated rather than the inmate’s last known place of residence, according to Joe Fulgham, communication officer for the House Republican Caucus.

The Democrats are not sharing their progress, Fulgham said.

The General Assembly is statutorily required to convene before their own Nov. 7 deadline in order to approve district maps with enough time for candidates in the redrawn districts to meet residency deadlines.

Delaware state law requires that candidates for the House of Representatives and Senate live in their constituent district for at least one year prior to their election.

The next election for state representatives and senators will be Nov. 8, 2022. Every seat in both houses will be up for election, with those elected becoming the 152nd General Assembly.

If the General Assembly approves the redrawn maps on Nov. 7 — the last day for them to do so — incumbent General Assembly members who are drawn out of their current district would have just one day to move their primary residence within the redrawn district. If they fail to do so, those individuals could not meet the 1-year residency requirement.

Residency requirements could be further complicated if Democrats and Republicans are unable to reach a consensus by Nov. 7.

Candidates who manage to meet the residency deadline must file for state legislative primary elections by July 12, 2022. That means candidates would have eight months to decide to seek election and meet other ballot access requirements.

Those requirements include a $945 fee for members of qualified parties or a petition with the signatures of 1% of the district’s registered voters for unaffiliated independent candidates.

The General Assembly’s special session is the last of many steps in the redistricting process before the legislation is sent to the governor for approval.

Before that, the majority caucuses must craft their maps and submit them to their members for input and feedback.

They will then adjust the maps to satisfy their members and secure a consensus among their membership for approval before making their maps public.

Once publicized, the majority leadership must provide an opportunity for public comment, potentially make minor changes based on that input, and put the maps into bill form.

Once the bill is approved by the legislature, it will go before Gov. Carney for his signature.

Charlie Megginson covers government and politics for Delaware LIVE News. Reach him at (302) 344-8293 or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @cmegginson4.

Share this Post