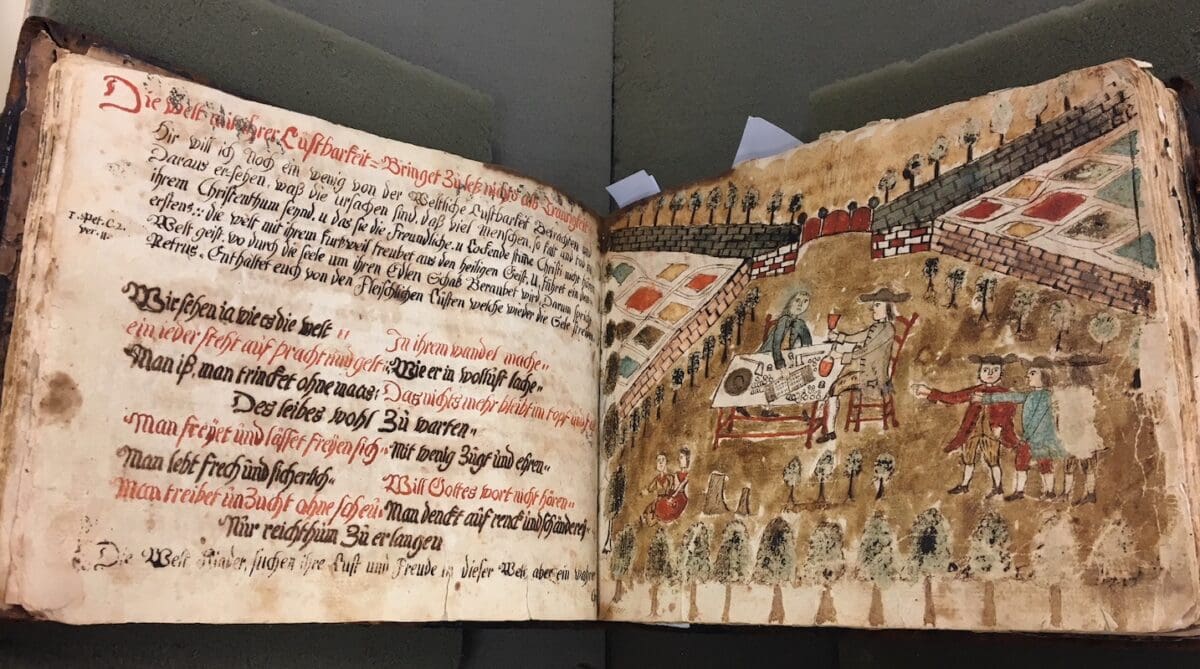

A manuscript by Ludwig Denig offers rare insight into life two centuries ago. (Winterthur)

A shoemaker’s remarkable record of life, art, music and faith in 18th-century Pennsylvania has a new home at Winterthur, and it’s also on its way online.

“There’s no manuscript like this that has survived,” said Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, who is leading the project to understand and digitize a manuscript created by Ludwig Denig.

The understanding included a recent half-day multidisclipinary study day at Winterthur.

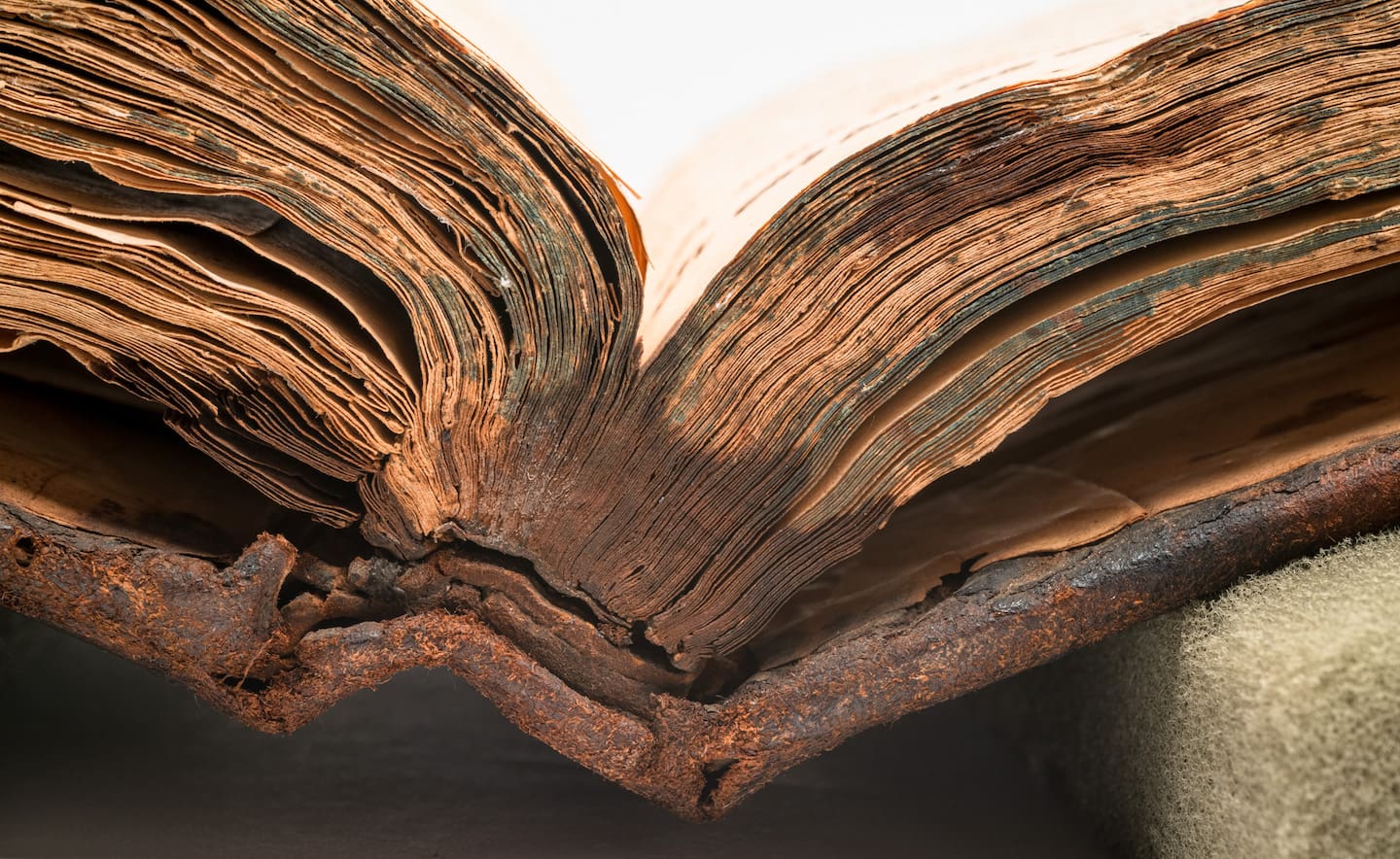

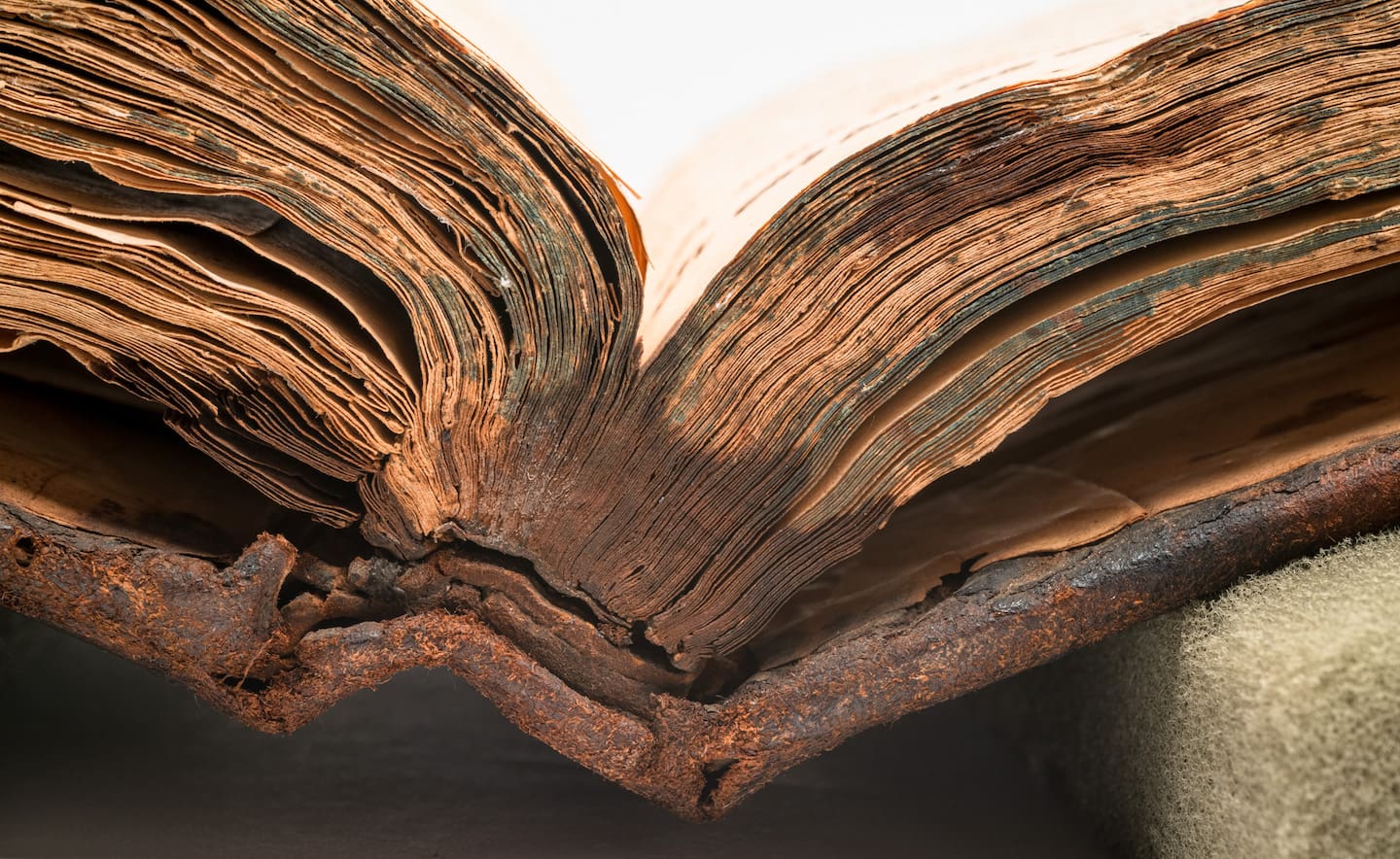

The manuscript, begun in 1784, is too fragile to display. “Given the document’s fragility, each turn of the page threatens its physical integrity,” Winterthur said in announcing the study day and explaining the importance of the digitalization and enhancing interpretation of its various facets.

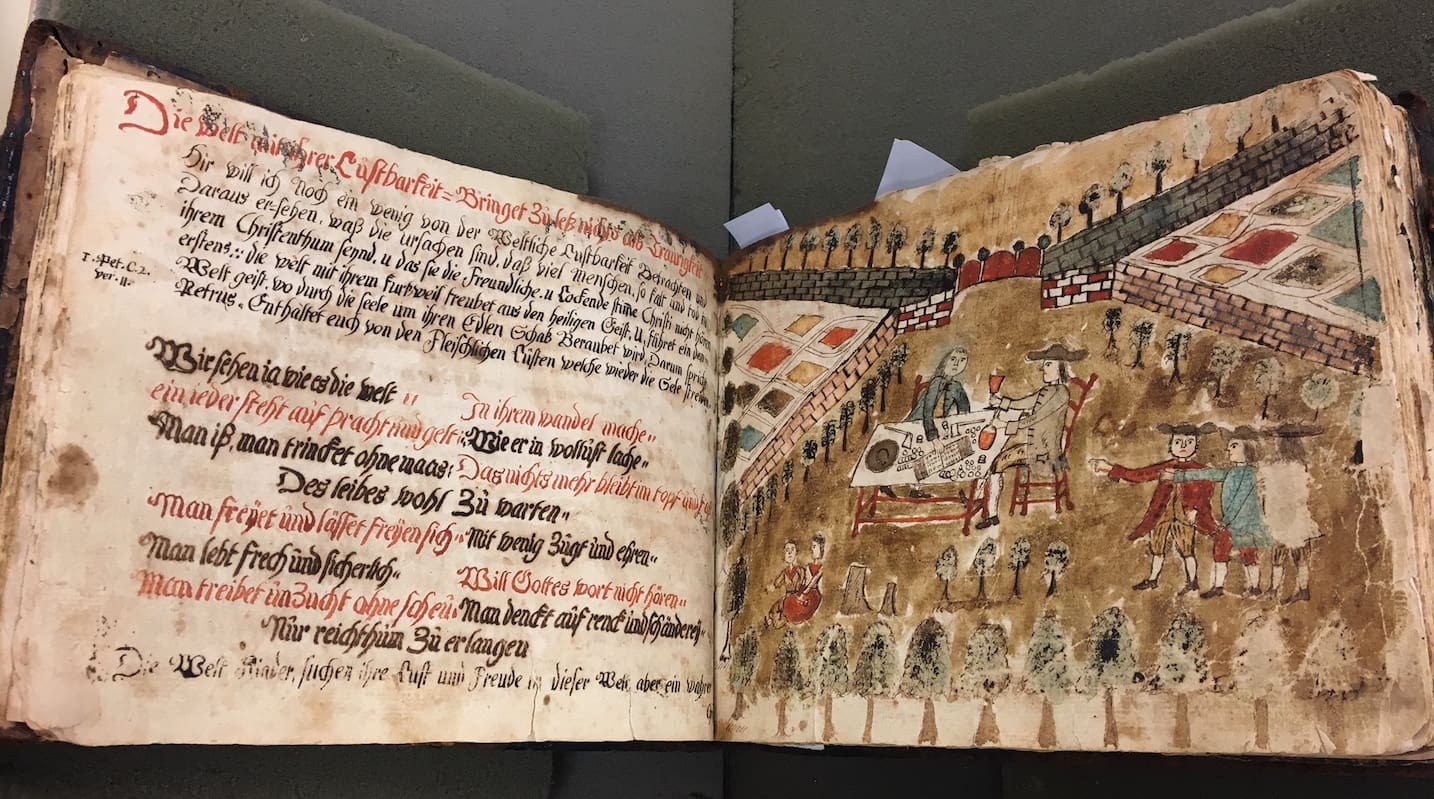

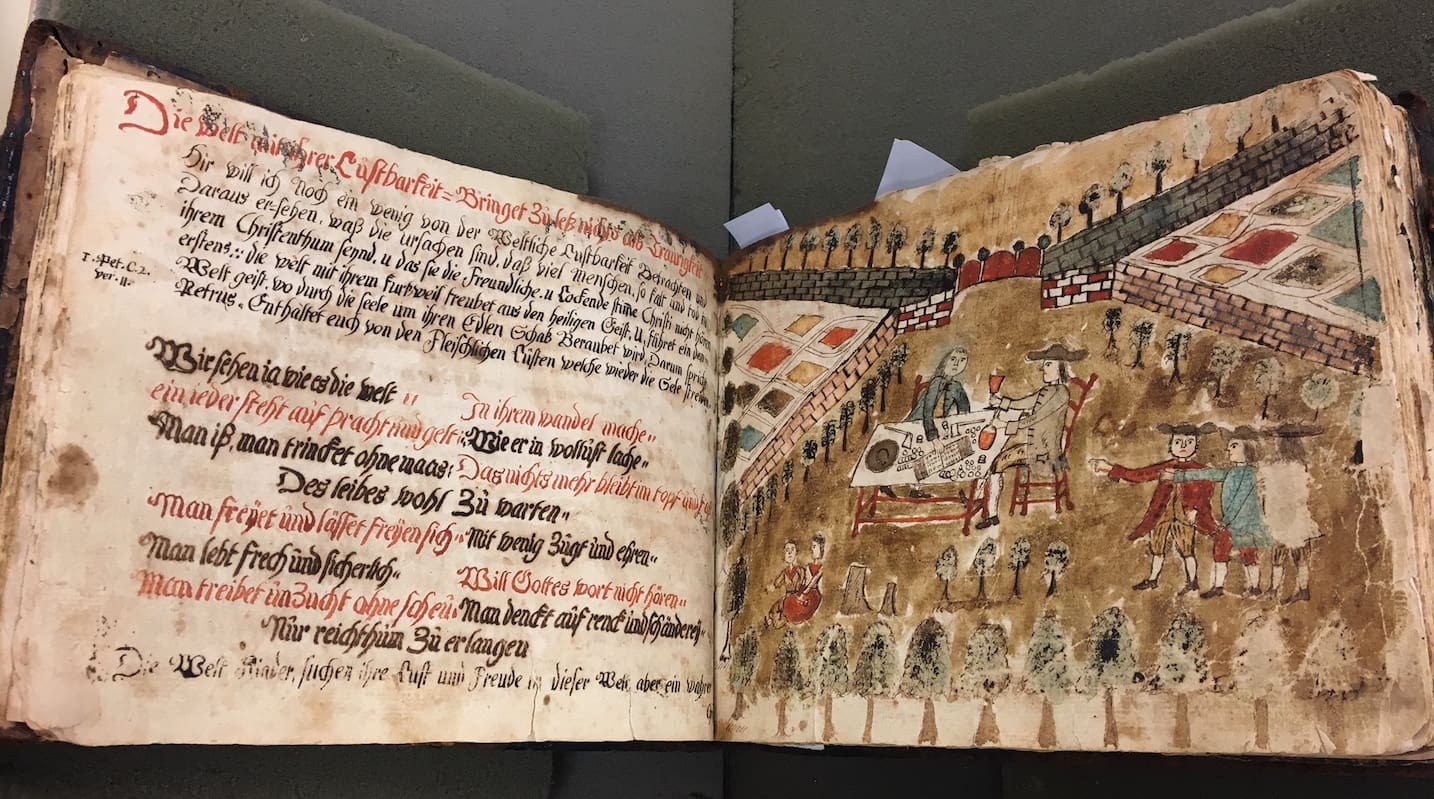

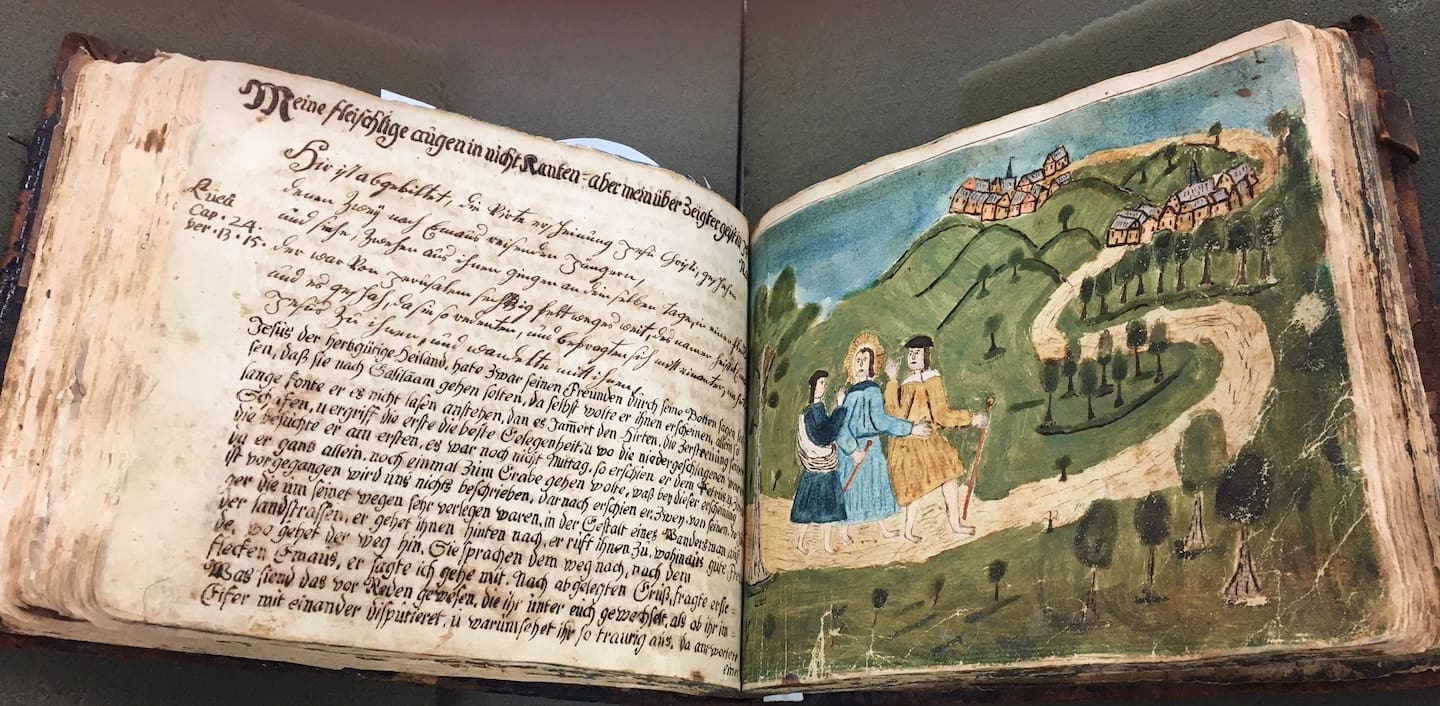

Ludwig Denig wrote his manuscript in German, in a script called Fraktur. (Winterthur)

Ludwig was born in 1755 in Lancaster. He started the manuscript in the 1780s, and he died in 1830 in Chambersburg, where he also worked as an apothecary.

The work includes more than 300 pages made from rag paper and leather bindings that he did himself. Some pages are blank, and others incomplete, with perhaps an illustration and title but no text.

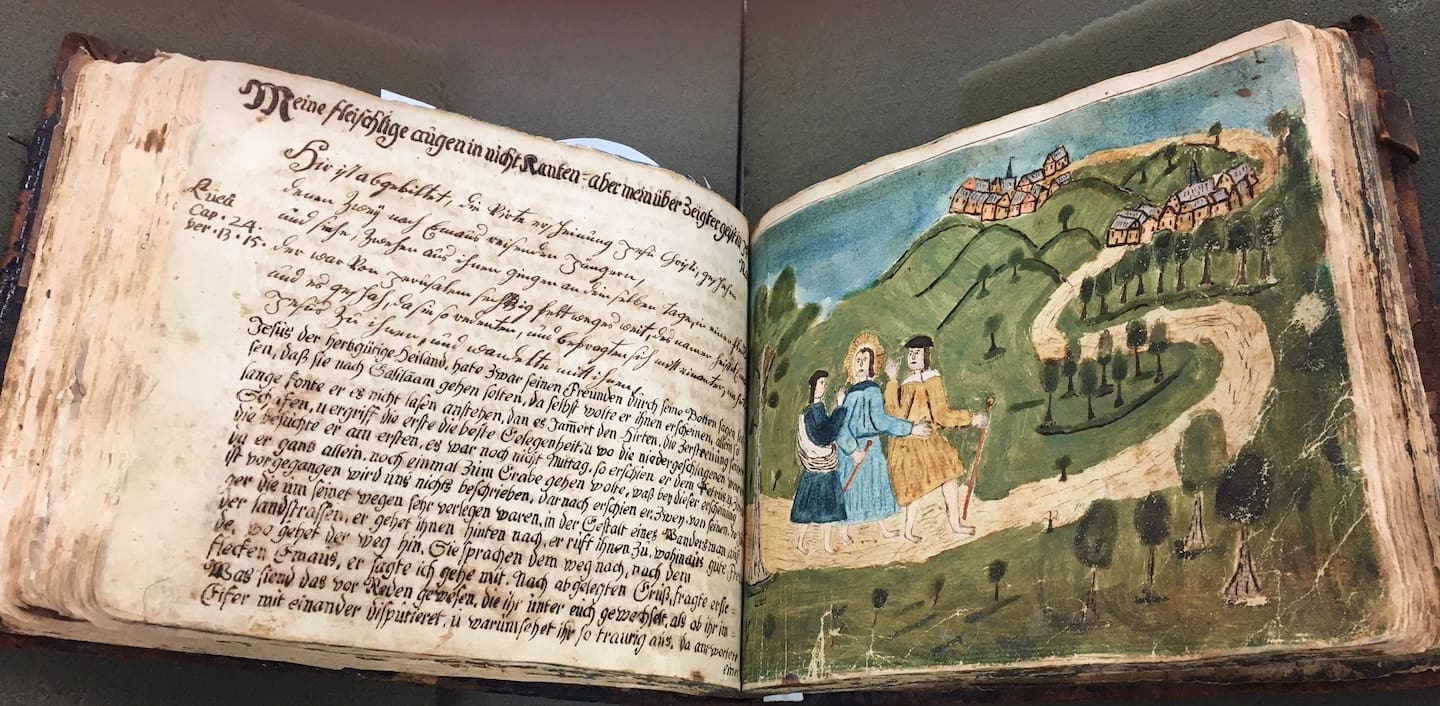

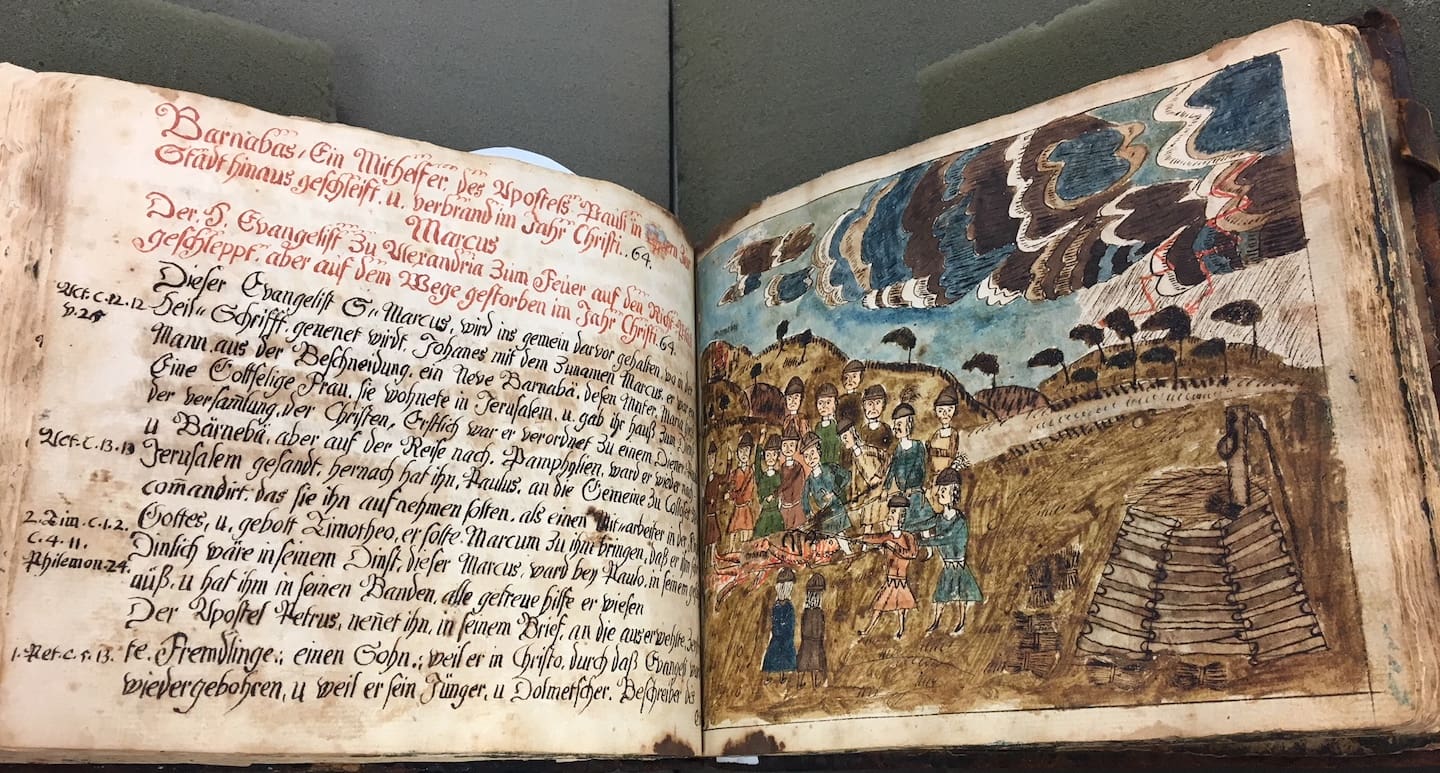

“His Pietist leanings and his connections to both Lutheran and Dutch Reformed churches surface in the book’s hymns, personal and devotional texts, and ink-and-watercolor drawings of Biblical scenes and martyrdoms, which include events from the Passion of the Christ,” Winterthur blogged.

“It was made to be used by family and friends,” she said, citing hymns written for multiple voices.

The manuscript depicts life in Pennsylvania, in what was then America’s frontier. (Winterthur)

Christopher Herbert, assistant professor of music at William Paterson University of New Jersey, traced most hymns to published works but concluded one was written by Denig and another was copied from a private collection.

Ludwig wrote in German in a script called Fraktur, an ornate font that is considered hard to read. That’s why the website, expected in 2024, will feature a transcription of the German and a translation into English. It will also include professional recordings of the hymns and essays by scholars.

He was a self-taught artist, said Delamaire, curator of European and American art at the Carnegie Museum of Art and previously curator of fine art at Winterthur. Examination of the drawings show him exploring techniques and copying from prints. “He’s trying to figure it out as it goes,” she said.

The work “follows the rich tradition of illustrated medieval religious text and music, but it’s totally different,” she said, noting that Ludwig’s work stands out because his folk art shows the typical clothing of another continent and another era.

The Denig manuscript is too fragile to display. (Winterthur)

The manuscript was given to Winterthur by Alessantrina and David Schwartz and the Schwartz Foundation

It had stayed in the family until early in the 20th century, when it was sold. It was sold again in the 1970s, which eventually led to the publication of a two-volume facsimile titled “The Picture-Bible of Ludwig Denig: A Pennsylvania German Emblem Book.”

Delamaire doesn’t want to call it a Bible because, even though it quotes a lot from the Bible, it also has a lot of commentary.

Delamaire noted that a lot of the illustrations depict violence, perhaps a reflection of his living just blocks away from the 1763 massacre of Conestoga Indians and serving as a private during the Revolutionary War. Or, as Winterthur’s blog put it, “Could this proximity to violence have informed the contents of the manuscript?

The hymns “could be understood as a way for the community to heal,” she said, but then adding a point from discussion at the study day. “Some of the scholars were questioning that interpretation in a sense that maybe this is what we want to see.”

Share this Post