Wilmington Friends School, the oldest existing school in Delaware, will celebrate its 275th anniversary starting Sept. 5

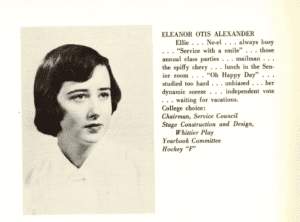

For Ellie Alexander Poorman, attending Wilmington Friends School means much more than just education – it means family, and generations of it.

The historic school, founded in 1748, is older than the country.

Friends will start celebrating its 275th anniversary Sept. 5 when it opens its doors for the 2023-2024 school year.

Poorman, 88, sent all four of her children and several grandchildren to Wilmington Friends, which is Delaware’s oldest existing school.

“You feel a great kinship with the school and its values, which are important to you and ones that you want to pass on to your children and grandchildren,” she said.

Those Quaker values the school is founded on – simplicity, peace, integrity, community, equality and stewardship – prepare people to connect with others and live a life of service while building confidence in young people, Poorman believes.

Over the centuries, those values created a nursery of sorts for leadership in the Wilmington community and beyond, according to “A Gift in Trust: Wilmington Friends School, A Celebration of our first 250 years,” written in 1998.

The school’s alumni include nationally notable journalists, politicians and government officials.

Poorman family members are among the 40,000-plus students who have attended the school since 1879, records show.

Wilmington Friends values

Wilmington Friends was among the Quaker schools founded around the country and in the British Isles in the 1700s, embracing the philosophy of George Fox.

He was an English dissenter and a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers.

When he lived in the 1600s, only the rich were educated, and Fox believed all children, both boys and girls, should be “that there be not a beggar amongst us.”

George Fox

Quakers in the Mid-Atlantic then “were aspiring for a society where all were welcome, regardless of religious belief or sharing common ancestry, that was peaceful and tolerant as long as we all agreed to abide by what we now call rule of law,” said Drew Smith, executive director of the national Friends Council on Education.

“Quakers believed that in order to achieve a religiously plural, culturally and economically diverse, and peaceful society, children needed to be educated to become citizens with agency and information, who could work together in adulthood to imagine a more ideal society.”

“Not until the late 19th. century was Friends a college preparatory school, and students attended in order to learn the basics: reading, writing, and “ciphering”–arithmetic,” said Terry Maguire, school archivist. “They might attend for months or years, until they had mastered those basics.”

Then, students came to learn the basics: reading, writing, and arithmetic. They might attend for months or years, until they had mastered those basics.

In the early 1800s, more than 2,200 payment vouchers were provided for poor children, for terms varying from three months to seven years, Maguire said.

About 400 of those payment vouchers were for Black children.

“That is not to say, however, that there was racial integration,” Maguire said. “On the other hand, Delaware public schools did not accept Black children until after the Civil War—so Wilmington Monthly Meeting provided what education was available for that portion of the Wilmington community.”

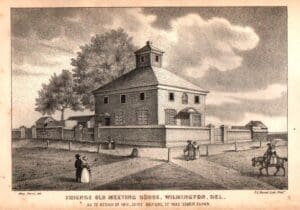

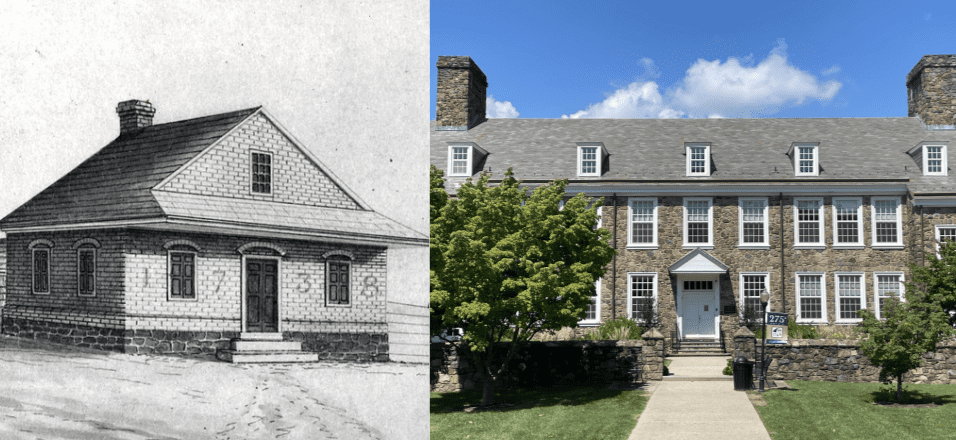

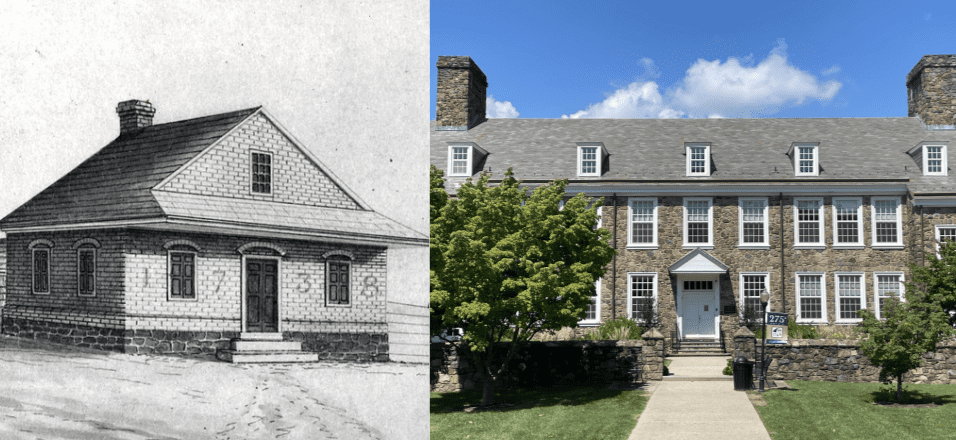

The first school building was a 24-square-foot structure that, in 1738, had been the first Meeting House. Within 10 years the congregation had far outgrown that building. After a new meeting house was built, the tiny first one became a two-room school.

In the 70 years following the Civil War, Wilmington Friends School grew, Maguire said. Its student population and academic divisions quadrupled. Faculty, staff and costs increased by a factor of 10. Extracurricular organizations–sports, publications, music, and drama– blossomed.

Eventually, the school needed more space and moved in 1937 to 101 School Road in Alapocas.

Since the move, there have been at least eight major expansions of the campus facilities and the school now is in process of building a new, bigger lower school building.

20 members of the Wilmington Friends School went to the Dominican Republic in July to immerse themselves in Spanish and help teach English in a classroom there.

The value of silence

Although it’s a Quaker school, today only 10% of the families the private school serves identify as Quakers.

“We studied the Quaker religion, and we have great respect for the Quakers and what they offer to the world and to education,” said Poorman, who graduated from the school in 1953.

Ken Aldridge, head of the school, said Quaker values, which they refer to as SPICES, are ingrained into Quakerism and the school.

There’s two ways of perceiving the Quaker ethos, he said.

“There’s the spiritual sense of that of God in everyone,” he said, “and then there’s the secular sense of there’s good in everyone.”

One value they do not include in that list is silence and being reflective in silence, but it underscores the school’s approach to almost everything.

“Quakers use silence quite a bit,” Aldridge said. “We use it as a teaching tool to students, and all three divisions have a weekly meeting for worship, where they may be posed queries to think about things that may be on their mind, their relationship to others, and just their own self-reflection and self-awareness along with things that may be going on in the community at large.”

Naturally, younger people find it difficult to sit in silence, Maguire said, but usually well before they leave Friends School, they have come to value quiet, to retreat into their own minds, and to listen to the sharing of others’ thoughts that might, or might not, occur at each Meeting For Worship.

“Often before each class or committee meeting, a brief silence is observed,” Maguire said. “To start the business of the class or meeting then seems easier.”

He called it “a mental cleansing of the palate.”

Building confidence

Poorman said she couldn’t imagine a family in Wilmington wanting to go to any other school since Friends not only provides a great education, but also grows a child into a meaningful member of the community.

The core of Quaker education adds a responsibility of service, which is giving to the community around you, she said.

Service can help build the confidence of a child by having him or her interact with others outside their bubble.

Poorman said she remembers a lot of presentations where young children were speaking in front of and to large groups of people, another confidence builder.

One of her favorite memories of community service, she said, was taking trips to Philadelphia to help paint and spruce up the apartments of city residents.

“We slept in a church on cots, which I’ll never forget,” she said. “Our English teacher wanted us to learn the responsibilities of good stewardship and working with other people, working with folks from other nationalities.”

Over the decade of Aldridge’s tenure at the helm, the school has increased the number of service trips.

In the summer, students typically have the option to go to several places around the world, such as the Dominican Republic, Cape Town, Pretoria and Madikwe in South Africa.

“We’ve been to El Paso, Texas a few times, and our students have an opportunity to learn all the complexities of immigration at the border,” Aldridge said. “They’ve talked to Border Patrol. They’ve talked to those who are in processing. They talk to attorneys on both sides. They talk to judges.”

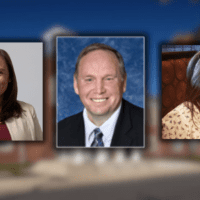

Meredith Rosenthal, who sent her two children to Wilmington Friends, transferred them from a Montessori school.

She had nothing but nice things to say about the Montessori school, but felt like Wilmington Friends does a better job at creating an environment that’s more hands-on, with more discussions and smaller class sizes.

“My kids were really looking for experience learning, instead of somebody just sitting at the front of the classroom and teaching to them,” she said. “In the aftermath of COVID, Wilmington Friends figured out how to keep the kids engaged, even when it was remote for a period of time, but then they also brought them back fairly quickly compared to other places.”

Comfort zones

One of her favorite aspects of the school, she said, is how engaged the community was and how everybody got to know her children.

“When you see a Wilmington Friends’ report card, it just shows the teachers know your kids so well,” she said. “I have two very different children who learn differently and they have different personalities, and it’s reflected completely in their report cards and the messages and comments from teachers.”

Poorman, who entered Friends as a freshman in 1949 and graduated in 1953, still recalls some of her favorite teachers.

George Reeser was a history teacher she had who she remembers as being very strict, but really just wanted students to work hard to achieve their full potential.

She recalled Ed Savery, a biology teacher with whom she had a strong connection.

“And then of course there was my beloved Miss [Frances] Baird, who was the Latin teacher,” Poorman said. “When I entered Friends, everybody had already had a half year of Latin so I struggled, but she was always supportive and always such a lovely, gentle person that encouraged you.”

Rosenthal agrees that the school encourages students to get out of their comfort zone. She points to the school’s sports requirement.

“You get to see kids that never knew they could play a sport maybe become the best on the team by the time they’re juniors or seniors,” she said. “My daughter probably never would have played field hockey in public school, but because she was required to in middle school, she found that she loves field hockey. She loves being a part of a team.”

Poorman said it’s a long-standing tradition for students to participate in athletics.

Decades after graduating, she ran into a woman who had attended Tower Hill School who told her, “I know you. We used to play against each other in high school.”

Rosenthal said her children learning to express themselves is probably her most cherished benefit from attending Wilmington Friends.

“Their commitment to the environment and to peace has made my kids become really well-rounded,” she said. “The students there just have this ability to talk to people and engage with people.”

While Quaker schools exist across the country – many children of presidents attend Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C., for example – the schools operate independently.

“While the Friends Council of Education is a venerable and much respected institution, in which educators from different schools exchange ideas and practices, it does not issue any imprimaturs of what shall or shall not be taught at which levels,” Maguire said. “In neither Quaker religion nor Quaker education is there a hierarchy of authority. Collaboration is encouraged, not mandated.”

Quakers have always held egalitarian beliefs with little regard for caste social distinctions. They believe God is in every person, and intermediaries such as priests or ministers are not necessary.

“Being educationally self-sufficient is the practical equivalent of that religious independence,” Maguire said.

- 1972

- 1940s/50s

- 1913

- 1748

Continuing to build

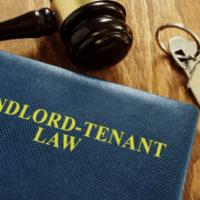

Wilmington Friends rarely sparks angst, but the 2019 sale of its lower school property for $50 million to biopharmaceutical company Incyte has upset its Alapocas neighbors.

Many fear the fives-story, 400,000-square-foot building Incyte wants to build will ruin the character of the community, cast unwelcome light into the neighborhood at night and won’t have enough parking spaces for the 1,050 employees the company plans to move into the location.

Incyte wanted the property because its headquarters are nearby.

As the Incyte plans move through regulations, Aldridge said Friends will focus on its expansion plans by building a new, two-story lower school over 18 to 24 months once the project is approved by government boards.

“We’re not looking to increase enrollment, but rather to accommodate the current program and size of program and create a new state-of-the-art lower school building on our main campus,” he said.

Attendance at Wilmington Friends is pricey.

Tuition ranges from $11,140 for its preschool three-full-days program to $34,230 for ninth through twelfth grade students.

“We do offer financial aid for families, and that’s one of the long-standing traditions of the school,” Aldridge said. “We can go back to the late 18th century, early 19th century, to the history of the school where vouchers were being offered for people to attend school.”

Almost as long as Wilmington Friends has been in existence, he said, offering financial assistance for people who can’t afford the school has been a valued promise.

Wilmington Friends has been a hallmark of Delaware education and the history of the First State, Poorman said.

“The reason that our state was founded and people came into the new country and settled here was largely for all the religious freedom as well as good education,” she said. “Friends fills that need, and unfortunately there still seems to be a need that our public schools can’t fill.”

Notable alumni

Wilmington Friends’ notable alumni include:

- Adam B. Ellick: correspondent for The New York Times who filmed a documentary about Malala Yousafza, a female Pakistani education activist who won the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize laureate at the age of 17.

- Tracey Quillen Carney: First Lady of Delaware.

- Linda Holmes: NPR personality and writer.

- Matt Meyer: New Castle County Executive who is running for Delaware governor in 2024.

- Crystal Nix-Hines: United States Ambassador to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Daniel Pfeiffer: politician who served on Barack Obama’s administration and co-host of Pod Save America with Jon Favreau, Jon Lovett and Tommy Vietor.

- Carol Quillen: president of Davidson College.

- Louisa Terrell: American lawyer and government official who’s director of the White House Office of Legislative Affairs under President Joe Biden.

- Mabel Vernon: American suffragist, pacifist and a national leader in the United States suffrage movement.

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Jarek can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at (215) 450-9982. Follow him on Twitter @jarekrutz and on LinkedIn

Share this Post