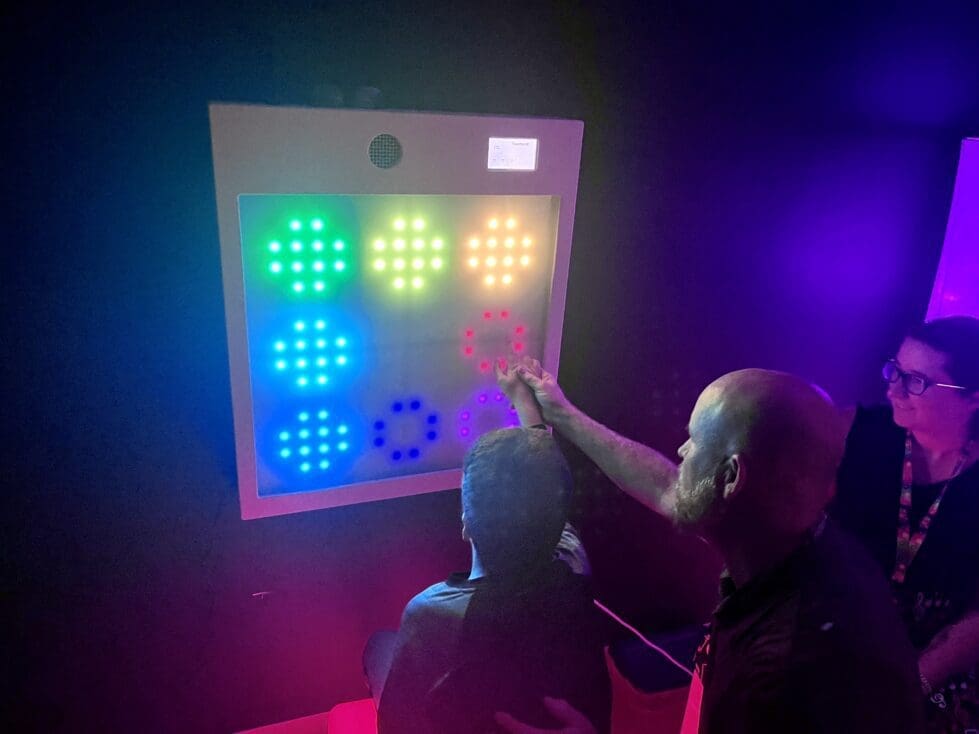

John G. Leach’s Tom Winkler guides student Grayson Otto’s hand as he makes music using the digital board in the school’s sensory room. (Jarek Rutz / Delaware LIVE News)

A New Castle County school has debuted a sensory room designed to help disabled students better recognize things they see, hear and touch – and become more confident in acting on that information.

Colonial School District’s John G. Leach School is home to 88 special needs students, ranging in age from 3 to 22.

Their needs range widely, one reason Principal Ginny Schreppler says the school continues to push itself to be at the cutting edge of specialized education with things like a sensory room.

“We are a restrictive environment, but that’s because every single one of our students here has needs and they are the 1% of the population,” she said. “We can provide a really high staff to student ratio and intensive wraparound and therapeutic services.”

That ratio is three to one.

The school’s new sensory room, which cost about $22,500, was converted from a storage room.

- The first section of the sensory room includes a station for students to run their feet and hands through. (Jarek Rutz/Delaware LIVE News)

- Just two students can be in the sensory room at a single time. (Jarek Rutz/Delaware LIVE News)

- The middle section of the sensory room includes a vibro-chair, bubble lamps, and a digital board. (Jarek Rutz/Delaware LIVE News)

Most of that money was used to purchase the equipment that fills out the room, including the main attraction, a comfy lounge chair with a high-tech component.

What’s in the sensory room?

About two feet from the chair is a large box speaker that plays music and is wired to send vibrations to the chair that build and fall with the rhythm of the song.

It’s not just gentle classical tones. The music includes artists such as the Foo Fighters and Nirvana, or anything else a student requests or likes.

“Just like going to the gym, your senses need to be exercised,” said Tom Winkler, an occupational therapist at Leach. “Some students don’t even realize the capabilities they have until they try and actually test out their senses.”

Many of the Leach students are severely disabled, and almost none can talk or converse with others in a typical way, Schreppler said.

Grayson Otto, a student at Leach, frequents the sensory room.

Winkler said Grayson loves jamming to rock music. Grayson’s father describes him as a “Deadhead,” the nickname given to The Grateful Dead fans.

Feeling the vibrations of sound makes connections in the brain and helps strengthen hearing abilities, Winkler pointed out.

Leach already had a calm room for overstimulated students.

Winkler said the sensory room also helps with student anxiety, but that’s not its main point.

“Just like going to the gym, your senses need to be exercised,” Winkler said. “Some students don’t even realize the capabilities they have until they try and actually test out their senses.”

Once students realize they are capable of hearing melodies or putting together words or following a series of lights, for example, Winkler said their confidence in themselves skyrockets.

A lot of their sensory skills are “unlocked,” he said.

The room is divided into three parts. Each feature of the rooms is specific to one of the five senses.

The entry zone has rubber mats on the floor that are spiked with different patterns. Students can run their feet through them.

About four feet up, the wall has miniature versions of the mats for students to pass their hands through.

A large padded swing in that first section helps develop a student’s vestibular system, critical to maintain balance and stabilization.

The swing helps students become more comfortable with handling and adjusting to movement.

While some features may seem to be random, Schreppler emphasized that everything is purposefully designed.

She said the combination of the black walls with a limited number of textured sensory tiles ensures that students aren’t overly stimulated. They can easily be overwhelmed and forget the purpose of each stimulant.

Striking this balance was one of the main challenges in constructing the room, Schreppler said.

In the second section of the sensory room, in addition to the musical chair, is a multi-purpose digital panel.

One of its features allows the students to drag their hands along the board.

As they do, a beam of neon light follows the path of the hand, and music plays in different pitches depending on where a student’s hand touches.

One feature of the board is a grid of colored squares set up like a keypad. When a student touches a specific section of the board, and a number corresponding to the position of the square will pop up at the bottom of the screen.

That also teaches cause and effect, as well as positioning of the numbers, which mimic a cell phone keyboard.

The digital board also can be used to create beats.

In that mode, each square has the sound of a different musical instrument and melody.

Once a square is tapped, that instrument and rhythm is locked into a program. The student can tap additional squares to add to the songs.

Across from the vibro-chair are two rows of panels that feature soft, colorful, gel. Students can press on it and watch how their touch affects the movement of the gel.

The top row is for students who can stand, while the bottom was designed for students in wheelchairs.

The middle section of the sensory room also has three massive bubble lamps, also designed to stimulate the student’s sense of sight. The students do not handle them.

The last section, the smallest, is home to a computer that has a button and switch attached.

When the student slaps the button or flicks the switch, different designs appear on the screen.

“This really helps students understand the cause and effect of their actions,” Winkler said. “The first level is them being able to use a switch and notice ‘If I hit this something happened.’”

“The next one would be ‘If I hit this one, it moves it and if I hit this one, it selects it,’” Winkler said.

This allows students to isolate and focus on cause and effect.

Staff members are asked to enter a calm state themselves before entering the sensory room with a student. They also are asked to limit any additional sensory stimulants, and that includes turning off all devices.

Two students can be in the sensory room at a single time, and their visits typically are brief.

“10 to 15 minutes tops will be needed for somebody to stimulate their brain, and then they go back to the classroom a little bit more ready to learn,” Winkler said.

- A student uses the digital board to make music in the sensory room. (Jarek Rutz/Delaware LIVE News)

- The sensory room has a large padded swing that helps develop a student’s vestibular system, critical to maintain balance and stabilization. (Jarek Rutz/Delaware LIVE News)

- Panels of jelly-like mush in the sensory room that students can push around with their hands. (Jarek Rutz/Delaware LIVE News)

At the end of the day, Winkler said the room is really meant to be a place for students to practice using their sensory channels that they don’t typically use in a more controlled and focused environment.

Leach opened 71 years ago to serve students with polio.

Today, the school has a unique atmosphere and nearly every worker seems to have some sort of specialization.

Not only do educators work at Leach, but occupational therapists, speech language pathologists, physical therapists and even student workers from other schools who engineer and build wheelchairs and equipment.

“Innovation is a buzzword and it is very much a verb,” Schreppler said, “but we’re really transformative with the times.”

She said the biggest challenge in creating individualized education for each student is communication.

“A lot of times our students don’t interact in a traditional communication method, so especially with our newer students it takes us a little bit of time to unlock what their behaviors and their actions are telling us,” she said.

The school itself needs more space to remain innovative.

Winkler said school officials already are working on the design of a new building that will give them room to create more need-specific spaces like the sensory room.

One reason: Many wheelchairs do not fit in through the narrow doorway of the sensory room.

“Due to the nature of our population we have to be individualized, which allows us to inherently be innovators in determining how to meet our students’ needs,” Schreppler said. “We are a family here and this is a collective experience that we’ve all worked hard to bring to our students.”

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Jarek can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at (215) 450-9982. Follow him on Twitter @jarekrutz and on LinkedIn

Share this Post