The cables on the Indian River Bridge are about as tall as the blades on the wind farm turbines will be, officials said Tuesday.

Whether you are a big fan of offshore wind power or you want all those turbines gone with the wind, a special meeting held by Rehoboth Beach officials offered insight into the projects and processes to create them.

The four-hour meeting revolved around the three projects proposed off Delaware’s coast and ultimately functioned as an illuminating primer on the issue. Watch it here.

Organized by Rehoboth Beach to create a shared pool of information for future discussions, the event allowed state and federal government, the industries proposing the projects, local officials, researchers and opponents to talk from their points of view.

Most of it amounted to congenial sales pitches given by self-assured lecturers.

Occasionally the talks veered into emotional waters, especially over the location and heights of the turbines.

“That pristine sunrise will never be the same,” said Ocean City Mayor Rick Meehan. “It will look like a backdrop from ‘Star Wars.'”

The farms have proved to be contentious issues for Delaware beach towns that will deal with the impact of two already announced projects: US Wind’s MarWin farm offshore Maryland and Ørsted’s Skipjack wind farm offshore Delaware and Maryland, as well as a recently announced Garden State project from New Jersey.

The US Wind and Ørsted projects will cover 125 square miles, said David Stevenson, director of the Center for Energy Competitiveness at the Caesar Rodney Institute, and an unapologetic opponent of the wind farms.

That area will have turbines placed a mile away from each other.

But even as US Wind and Ørsted glowingly described their efforts and government agency reps explained that the public does have input, Meehan and Terry McGean, Ocean City’s city manager, urged Delaware not to be complacent.

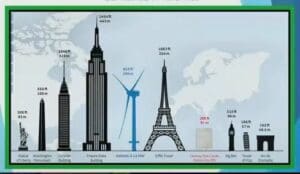

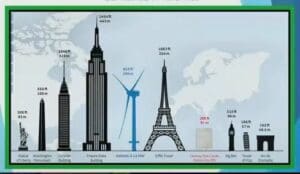

A graphic from Ocean City, Maryland, shows how the size of the offshore wind turbines compares to its tallest building, the Century One Condominiums.

Offshore wind turbines

“This is a very important issue for all of us, and it’s one that we tend to take very seriously,” Meehan said. “We need to really look at the future and, yes, there’s money being spent. Yes, they can provide money for different projects, but can you really buy the future? I really don’t think you can.”

Despite talk about replacing aging facilities, improving the environment and clean energy, the wind farms are not economically viable without substantial government subsidies for the builders, McGean said.

Ocean City has been fighting the Skipjack project for more than a decade, partly because of fears the ocean view will be ruined and hurt tourism and property values.

Information frequently changes about how many turbines will be installed, how tall they will be and how far offshore, McGean said.

For example, he said, the town was told that US Wind was going to put 77 turbines as close as 15 miles from shore. But the company’s federal application said 114 turbines would be installed 11.4 miles from shore.

On Tuesday, US Wind’s Mike Dunmyer told the meeting there would be 121 turbines in that project.

The Skipjack project will use 69 turbines that will be 20 miles from Ocean City’s coast, but could be closer to Delaware’s coast. All other information about the project is redacted in Ørsted’s application for Maryland subsidies, McGean said.

That project’s federal construction and operations plan is not yet available to the public, he said.

The Garden State project, owned by Ørsted and New Jersey’s PSEG gas and power utility company, will have turbines 12.7 miles off of Delaware’s coast, McGean said. No plans for the development are available, he noted.

One sticking point for coastal towns is the size of the turbines.

US Wind’s Dunmyer told the group that their application was going to ask for approval for two types of turbines, in case the latest design — at 938 feet tall — is available.

McGean said Ocean City was told in the beginning that it would be facing 3-megawatt turbines that no one could see from 10 miles away. Now the town has been told it will be getting 15- to 18-megawatt turbines visible from 30 miles.

No plans reflect the newest turbines, which can be 938 feet tall, he said.

“The visual impact of these wind projects can no longer be denied,” McGean said.

McGean and other officials said those with concerns should get involved with the process.

Ask four questions, McGean said:

- Where are the turbines and how close will they be to our coast at full buildout?

- How big are the turbines, both hub height and full height when the ROTOR is fully vertical?

- How many turbines are planned in full buildout?

- Where will the power make landfall?

Meehan said the town supports clean energy and wind farms, but not at the expense of the community.

“If these turbines are built, they will be the tallest structures in the state of Maryland. It’s unacceptable and it’s avoidable,” Ocean City’s mayor said. “It can no longer be said that the turbines will not obstruct our natural viewshed. It’s clear and evident that it will.”

Cost to consumers

Stevenson, who lives in Lewes, said offshore wind ultimately will cost consumers more.

He pointed to U.S. Energy Information Agency material that said a wind farm that starts in 2027, which is right around the time the Skipjack and US Wind projects will be hitting, will cost power companies $137 per megawatt hour compared to solar at $36.

“It’s almost four times as expensive and that includes everything,” he said.

Those costs will trickle down to consumers, he said.

At the same time, Delaware will see a marginal number of new jobs, he said. The majority will be in New Jersey and in Maryland, where a construction base is being established in Baltimore.

Offshore wind is simply replacing onshore wind and solar power, Stevenson said.

There are advanced nuclear power options, carbon capture procedures and other options to reduce carbon dioxide, he added.

“This is not a Save the Planet situation where we build these projects or we don’t or if we build them further offshore,” he said.

There’s a calculation that shows that even if all the projects start producing, it would only reduce temperatures in year 2100 by .004 degrees celcius.

“We’re not talking about saving the planet here,” he said. “So don’t put that in your calculations.”

Stevenson played a video to show the impact of the turbines, which said they will be 50% taller than the Washington Monument and four times taller than the Indian River Bridge.

That will make them easily visible from shore during the day, his video said.

At night, the video said, red lights will flash to warn marine life and airplanes of the turbines.

He was accused of exaggerating the effect by several speakers, but said he took the images from US Wind documents.

The nighttime images, another speaker said, were exaggerated because they would be radio-controlled and only flash when airplanes were nearby.

The Garden State project will be a reality, Stevenson said.

“It’s not approved yet but there is an important factor in Skipjack and all these projects,” he said. “You have to begin production of these by the end of 2025 or you don’t get the 30% tax credit.”

Other speakers

Karen Baker of the federal Bureau of Ocean Management Energy, and Jennifer L. Holmes of the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, kicked off the session by describing how their agencies gather information and make decisions, as well as how the public can participate.

In short, BOEM (pronounced BOAM) identifies an area for wind energy leasing, an auction is held among companies who want to develop that area, and leases are awarded. The companies submit construction plans for the offshore wind farms that BOEM then reviews including environmental impact statements and must approve before actual construction begins.

Even though all that is happening in federal waters, Delaware does have some sway in much of that process, Holmes said, because of the federal consistency process — which allows states to intervene when a project has foreseeable effects — and rules relating to the Coastal Zone Management Act.

Because of the consistency program, DNREC is notified by BOEM about new proposals and is able to respond.

But the state has more regulatory authority over the project because the cables that will connect the Skipjack projects to the power grid will land in Delaware, Holmes and McGean said.

McGean said the state even has the right to demand concessions over the placement of the offshore wind farms.

Dunmyer, who lives at the beach, and Danni Van Drew of Ørsted described their company’s project. Both said they are expected to last 35 years.

Dunmyer in particular described the number of studies that the company has been doing on the ocean, the animals that could be affected and human endeavors such as fishing.

The turbines are expected to last at least 25 years, but with good care could last 40 years, Dunmyer said. When the turbines are at the end of their life, they will be pulled down and recycled, they said.

Dr. Jeremy Firestone of the University of Delaware’s School of Marine Science and Policy and Dr. Willett Kempton of UD’s School of Marine Science and Policy described their often-cited studies about the impact of offshore wind farms.

Betsy Price is a Wilmington freelance writer who has 40 years of experience.

Share this Post