Delaware has hired a consultant to evaluate their complex and historic funding formula for school funding.

The Delaware Department of Education announced last week it has hired a Virginia consultant to study the state’s public education funding system.

As today’s wisecracker would say: Good luck with that.

How the money trickles down to the classroom is complex, and it follows a funding system established in the 1940s.

The state’s population then was 286,000, compared to today’s 967,679, and that was 27 years before Delaware schools were desegregated, shoving Wilmington students into districts that are largely suburban.

“It’s a complicated topic that not many people understand,” said Neil Kirschling, director of policy and advocacy at Rodel, an organization focused on educational equity and excellence.

Delaware public schools rely on money from a combination of state, local and federal allocations.

Its unique funding formula also essentially follows the teacher rather than the student, paying more to a district for experienced teachers, who are attracted to newer schools and suburban schools.

As a result, students who have special needs or are learning English have received the same amount of funding as a traditional student, and the funding often punishes city and rural schools while rewarding suburban ones.

The funding has been a sore subject for decades on a variety of fronts, including advocates for the poor or high-need families as well as Republicans who believe the state should provide vouchers that allow parents to choose where to send their children.

The way schools are funded sparked a far-reaching lawsuit that resulted in more state funding for poor and special needs children and also triggered a statewide property reassessment.

The problem is not the amount of money devoted to schools, says State. Sen, Colin Bonini, R-Dover and a member of the Senate Education Committee.

It’s a lack of executing those resources properly he said.

“We have some wonderful teachers and some wonderful schools, but we also have some schools that, I hate to say it, are flat out failing,” he said.

With all that as a backdrop, the state said last week that it will pay $698,438 to the American Institutes for Research to analyze current policy and make recommendations for improvements, with a focus on equity for all students.

The institutes have evaluated school finance in 16 states and most recently developed state-specific cost models for public education in Vermont and the New Hampshire Commission to Study School Funding.

The reports examined alternative approaches to school funding, simulated recommended funding allocations for each district and determined local tax burdens to achieve recommended funding levels.

Secretary of Education Mark Holodick said this work will help Delawareans decide the best way to fund schools in the First State.

“Delaware’s school funding system is outdated,” Holodick said in a press release. “We know change is needed, but we must make sure the direction we pursue is the right one for our state. The work of this team will inform our state’s move toward a system that will best support all Delaware students.”

American Institutes for Research will analyze existing funding, compare Delaware’s funding to other states and include feedback of stakeholders and recommendations for improvements. A final report is expected in November 2023.

The biggest news in state education funding in recent years has been the Chancery Court lawsuit.

In 2018, a group of school reformers grew tired of talking and filed suits with state and county officials, saying the system wasn’t equitable. Plaintiffs Delawareans for Educational Opportunity and the NAACP of Delaware were represented by national law firm Arnold & Porter, the American Civil Liberties Union of Delaware and the Community Legal Aid Society.

Part of the suit was settled in 2020, with Gov. John Carney agreeing to add $25 million in state Opportunity Funding to help English learners and low income students. It is expected to rise to $60 million by the 2024-2025 school year.

Then all three counties agreed to reassess property in light of the court’s ruling that the state’s current reliance on property values violates Delaware law and Delaware’s Constitution.

One reason that’s a problem is that most property in Delaware was assessed for taxes on the amount paid when it was bought. That means none of the rise in property values is reflected in today’s taxes.

“The funding system that we currently operate on really works best when we have regular and recurring property reassessments,” said Sara Croce, chief financial officer at Milford School District. “Now that there’s ongoing reassessments, it’s coming to light that the funding system that we have has mechanisms in place, but they’re not working properly because of the lack of reassessment.”

The bottom line for local schools is that ultimately the superintendent, principals and teachers have little control over where funding is spent. Most school money is allocated to specific programs.

That means local schools also have little control over programs they may want to adopt to improve learning and raise achievement scores.

“The state is actually telling every single school how many of each type of position they can go out to hire for,” said Rodel’s Kirschling. “Rather than giving them a flexible pot of money, they are deciding how to best allocate the resources based on the local needs of that school.

Personnel is the biggest cost driver in education, as roughly 80% of allocated money goes towards hiring staff and providing a benefits package, said Kirschling.

District chief financial officers might be the only ones who really are comfortable with it, Kirschling said, and it took them decades to fully grasp it.

According to officials at the Department of Education, local education advocacy organizations, and school chief financial officers, here’s what you need to know about school funding in Delaware:

How much funding is there?

Money comes from various sources: 59% from the state, 33% from local taxes, and 8% from the federal government.

All those funds up for an annual allocation of $2.48 billion for schools.

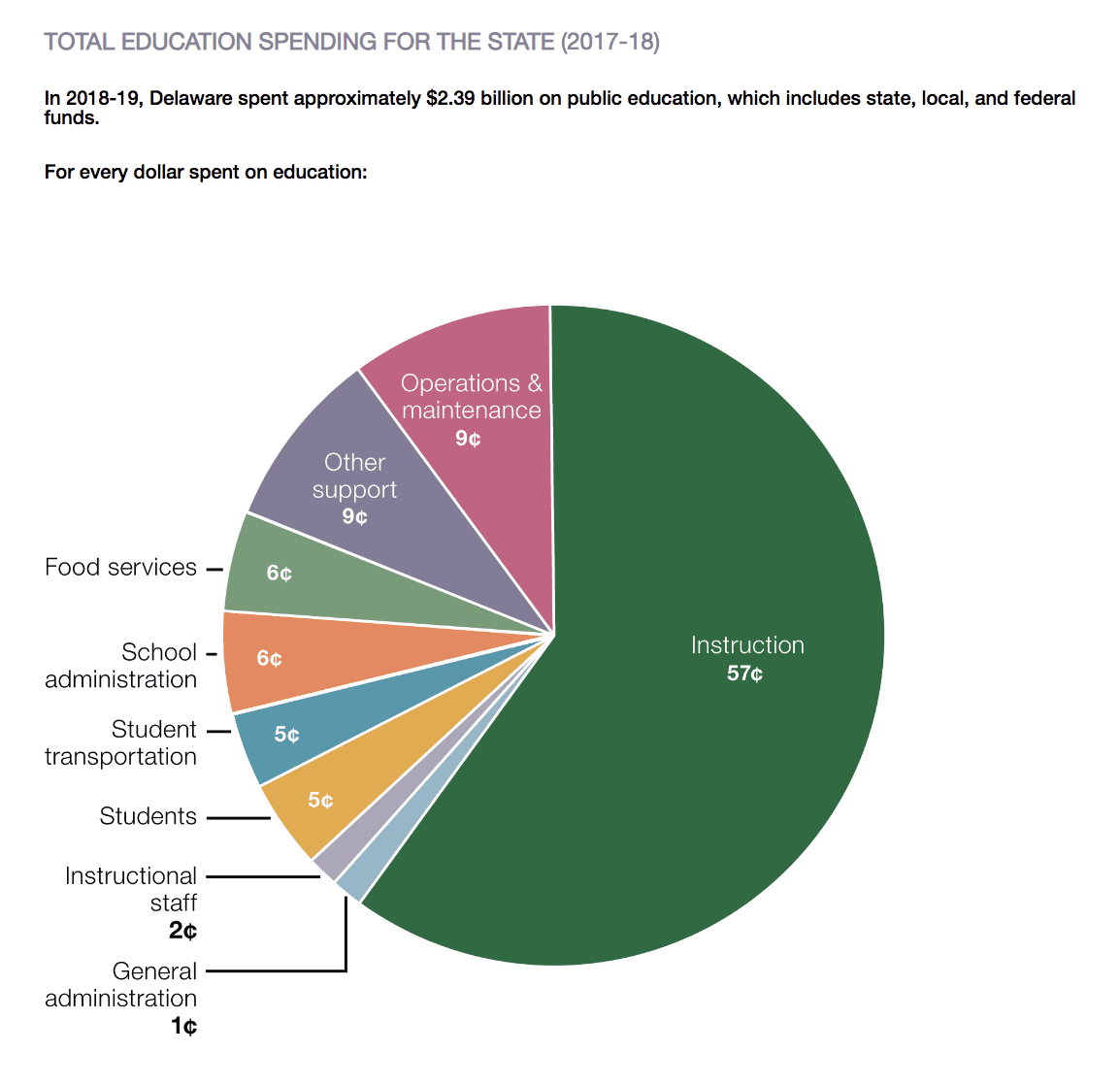

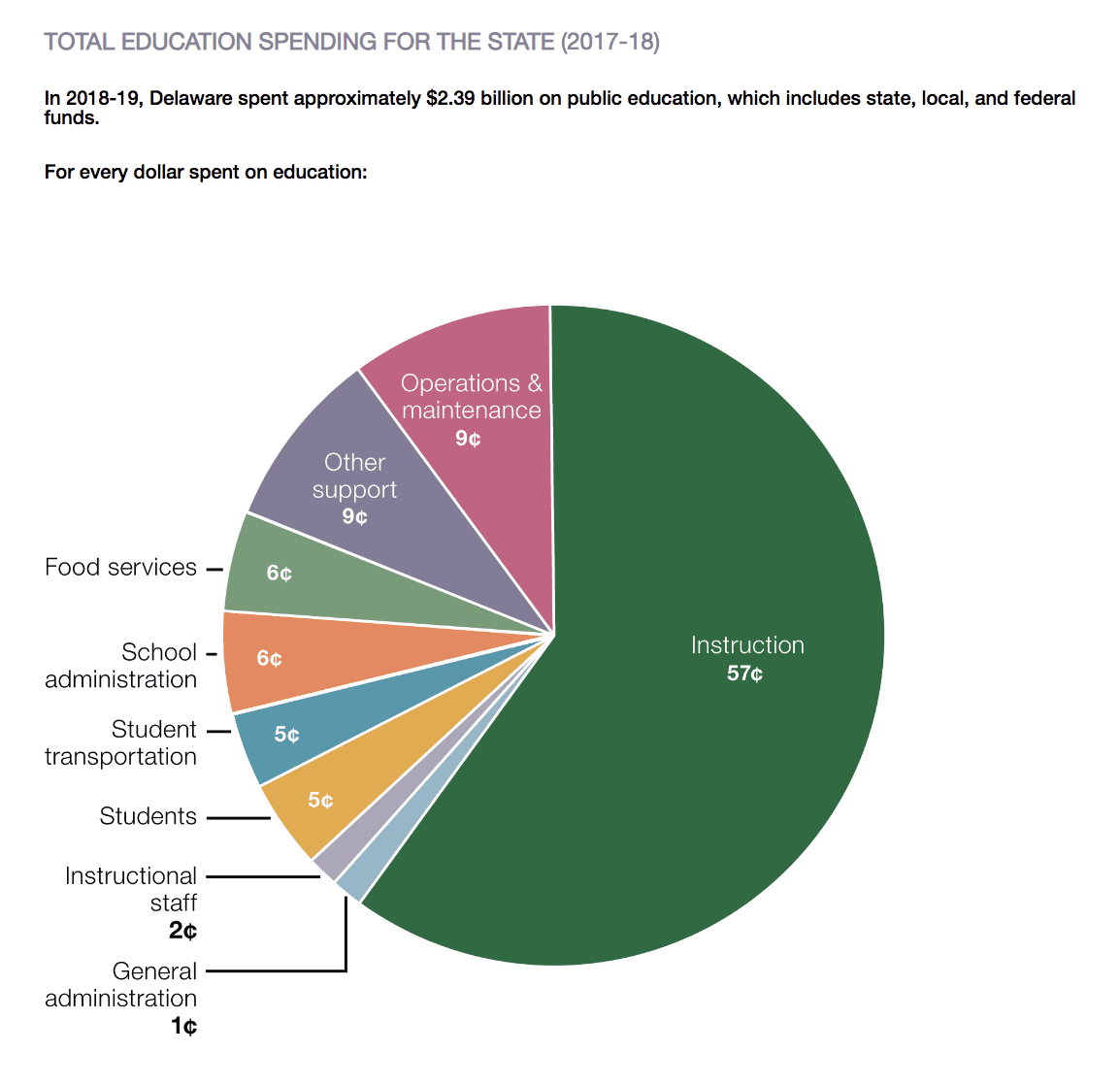

That number has been pretty consistent over the past five years. In 2018-19, the state spent roughly $2.39 billion on education.

Here’s how the money was divided, per Rodel:

The $2 billion plus in education funding is allocated into a number of areas. (Rodel)

Of the total, 86% of funding has a predetermined destination, whether that be paying staff salaries, transportation costs or energy costs, which all come from state funding, and cannot be shifted.

Only 14% of the budget is fully or partially flexible on a local level, and the actual number is probably lower for many districts.

“Once schools allocate the money for things that they have to use it for, it’s more like 4% flexibility,” said Laurisa Schutt, executive director of local education organization First State Educate.

If a school needs more reading specialists, but their formula says that they have to have a science teacher, then they have to have a science teacher, she said.

Capital projects, general operations and charter payments are a few of the things local funding goes towards.

Effect on achievement scores

Critics say the state’s budgets are not deployed in a way that helps Delaware’s students achieve, with white suburban students overwhelmingly doing the best on tests.

Delaware uses the Smarter Balanced Assessment to help districts identify what students are proficient in areas like math and reading for students in grades three through eight. It measures how well students do against expectations for grade-level performances.

The 2022 scores, out this month, were dismal. State education officials characterized them as a baseline that will help them decide how to deal with lost learning because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2022, 42% of white students earned a proficient score on the Smarter Balanced math test, the assessment the state uses to determine proficiency. Just 15% of Black students and 21% of Hispanic students earned a proficient score, according to state data.

In ELA, 54% of white students scored proficient in 2022, while just 27% of Black students and 32% of Hispanic students did.

Related: Migrant students educated, supported in summer program

But race is not the only determinant. Those with unique needs did much worse on the assessment.

Just 15% of low-income students, 14% of English language learners, and 9% of students with disabilities met their grade level math standards.

In ELA, 25% of low-income students, 17% of English language learners, and 12% of students with disabilities earned a proficient score.

In Delaware overall, 24.32% of students are from low-income households, 16.86% have disabilities, and 10.38% are English language learners, according to the state report card.

Failure in early grades to grasp basic reading and math skills often translates into a lack of learning throughout school and ultimately lower income jobs and a harder life, education officials say.

About a quarter of low income students and roughly a third of English language learners do not graduate high school in four years.

The settlement established a weighted funding system where special needs, low income, and English language learning students will get additional funding.

The Delaware ACLU stated it was “pleased” with the settlement.

“Our funding system must be designed to meet the needs of all of Delaware’s children, especially those who have historically been marginalized and underserved,.”

Sen. Colin Bonini, R-Dover, called the settlement a “complete disaster.”

“I thought that was 100% judicial activism and legislating from the bench,” said Bonini, who is on the Senate Education Committee.

He also said the settlement is going to be a “political firestorm” when the state completes its reassessments and people realize they have to pay higher taxes.

“If you think we need to spend more money on education and you think people need to pay higher taxes, then you should run for office and get that legislation passed,” Bonini said. “And if you can’t get it done in the General Assembly and you can’t get it done at the local school boards, then it shouldn’t happen.”

How state counts students

Delaware funds schools based on the number of student “units” in the state’s districts each year

Once the number of students are tallied and certified by the Department of Education, the state calculates each student as a “unit.”

Every unit is supposed to cover the financial needs of schooling one student, whether that be hiring teachers or installing a repairing HVAC systems.

Even so, for many districts, the amount of deferred maintenance required is a hefty cost.

For example, Christina School District has $372 million in deferred maintenance, Colonial School District has $195 million, and Smyrna School District has $87 million, according to Brandywine’s Chief Financial Officer Jason Hale.

How money follows teachers

While Delaware ranks 13th in the country in funding per student, with an average of $16,369,

Delaware’s neighbors – Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland – all allocate more money per student than the First State.

And while the state ranks 13th in dollars per student, achievement on tests ranks much lower than 13th.

Delaware ranked 36th in the nation in reading scores in 2019, the last year of complete and accurate testing data, according to U.S. News & World Report.

That same year, the First State ranked 37th in math scores.

Teacher salaries are on a pay schedule and increase with experience and credentials.

Teachers who spend more years in the classroom or are working towards a masters or doctorate degree are rewarded by climbing the pay scale, and observers say their pay can rise quickly compared to the average starting salary of about $33,000 according to Zip Recruiter.

“The state hasn’t really talked about the unintended consequences that when it allocates teacher positions to a school, it allows for the more experienced, more educated, more highly paid educators to drive resources unintentionally to the schools where they choose to work,” said Kirschling.

Often in Delaware, it plays out that the high poverty schools have less experienced teachers, he said.

Districts that attract and retain experienced, more highly paid teachers, are oftentimes already affluent districts, usually in the suburbs. They will receive more money from the state, while poor and inner-city schools are left behind.

That’s because in the state’s calculation of units, they place more value on teacher “units” that have more experience or credentials.

Why does this matter?

Because less experienced teachers tend to teach in rural or city schools, more experienced teachers often land in the suburbs.

This leads to a cycle of suburban schools always receiving more funding than rural or city schools.

And it leads to a cycle of teachers seeking positions in newer schools and more affluent areas.

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Jarek can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at (215) 450-9982. Follow him on Twitter @jarekrutz and on LinkedIn

Share this Post