Caesar Rodney students planting as part of their environmental studies. (Courtesy of Caesar Rodney School District Facebook).

Caesar Rodney School District is the only district in the country to be awarded a grant from the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation for habitat restoration and education.

The district will use that $227,000 to continue to restore underutilized space on 14 public school campuses within the district.

To do that, it will revitalize the EcoTeam Volunteer Corps, use traditional coursework, district professional development, and community outreach, grow a network of community partners and even hire students as seasonal workers.

“How do students really understand the impact of humans on nature if all they do is study in the classroom,” asked Dr. Todd Klawinski, Caesar Rodney’s environmental education specialist.

He is the district’s first staff member to exclusively focus on environmental literacy.

Klawinski defines environmental literacy as a result of meaningful environmental education.

The first part of environmental education, he said, is studying and creating initiatives related to outdoor education and getting kids and adults back outdoors throughout the year.

The other element, Klawinski said, is sustainability, and teaching or practicing with students the best practices for keeping a healthy ecosystem for animals and plants.

Environmental literacy is achieved when an environmental education program is meaningful and systemic, he said.

“It’s not just reading books in the classroom,” he said. “It means actually being involved and taking actions and going from what you learn in the class to applying those practices in your community to actually make a difference.”

This commitment to bettering the environment throughout someone’s life is what makes a person environmentally literate, Klawinski said.

Projects that use the grant money must provide benefits to wildlife with increased intent to target listed, at-risk, and priority species’ needs while increasing equitable access to authentic place-based learning for all students.

The money will also fund field trips to wastewater management plants, nature sanctuaries, conservatories and anywhere else that can get students out into the environment that they’re learning about.

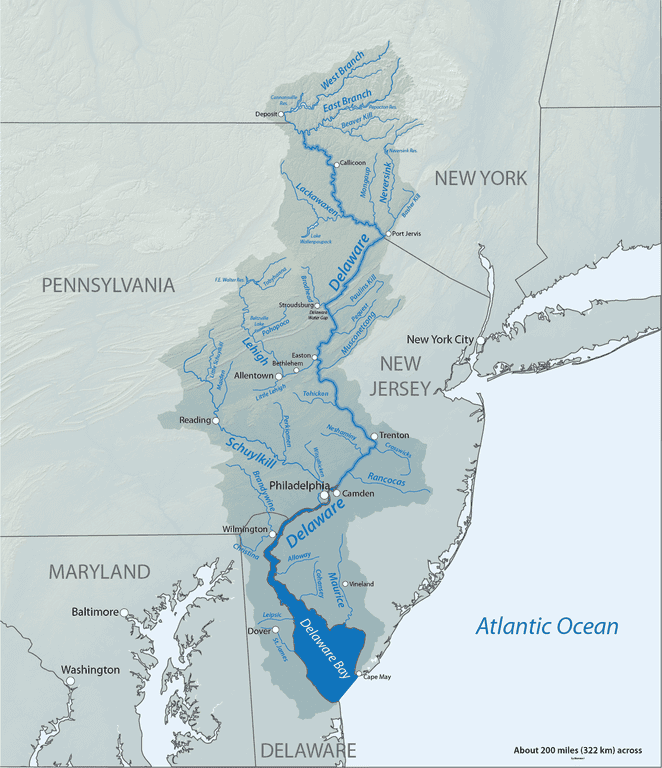

The grant will be distributed through the Delaware’s Watershed Conservation Fund, which supports projects that conserve and restore natural areas, corridors and waterways on public and private lands to support native and migrating wildlife, fish and native plants.

The fund also hopes the projects contribute to the social and economic health of communities in the Delaware River Watershed.

The watershed is 12,800 square miles and covers parts of Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. Much of that land includes areas with streams and creeks flowing into the Delaware River.

The National Fish & Wildlife Foundation has allocated $13.8 million to 36 different entities in Delaware, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

The Fish & Wildlife money also allows Caesar Rodney to hire five students as seasonal employees who could be part of a work study program to gain experience working in environmental protection and conservation.

As this would be a new initiative, details haven’t been completely worked out yet by the district.

The application process for the grant involved the district explaining their goals and what they plan on doing with the money, as well as partnerships they plan to form to assist in their environmental instruction.

Klawinski believes Caesar Rodney was approved because the foundation can see that educating students in public schools will be most likely to create wider community change.

While growing up, he said, students transition between two worlds.

“There’s one world, the intrapersonal world, which is their time to know about themselves and understand their thoughts and their feelings and you know, their health and their wellness,” he said.

Then in high school and towards college, their focus transitions to a world in which they want to function well and succeed in.

At that time, Klawinski said, young adults begin taking on more responsibilities, such as voting and earning money – and understanding how their actions affect people and the world around them.

“That’s why environmental education is so important,” he said, “They begin to feel more immediate connection to what’s around them, their local habitats, their school grounds, their own personal backyards, their town, their county, their state, their world.”

When students are educated about the environment, they become more conscious of their ability to damage, waste, and degrade the ecosystem around them, he said.

The grant includes an equity component.

“We want to make sure that we’re communicating to the community that outdoor work, outdoor pleasures and leisures are accessible to everybody,” Klawinski said. “Even to the point where we look at equity not from a socioeconomic background perspective, but from a personality standpoint.”

Children who might be very introverted can benefit from spending time in nature, which can serve as a destresser, he said.

Ultimately, Klawinski said, “We need our students to be prepared to deal with difficult ecosystem challenges that they will inherit long after we’re gone.”

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Jarek can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at (215) 450-9982. Follow him on Twitter @jarekrutz and on LinkedIn

Share this Post