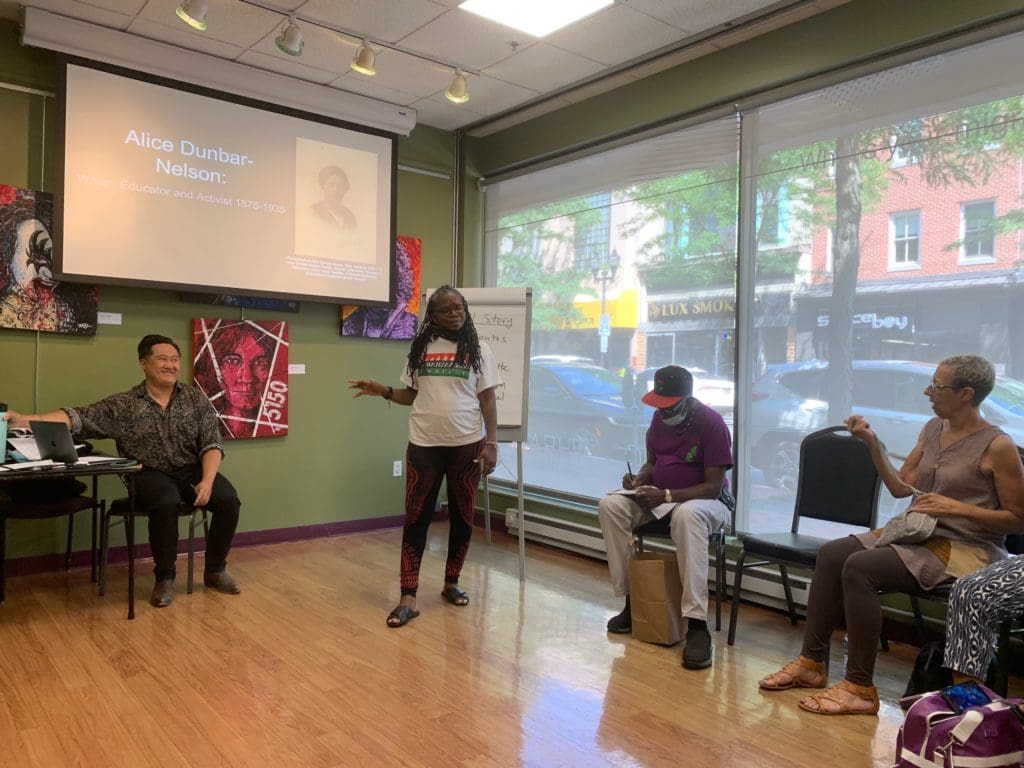

UD’s Dr. David Kim, left, listens to TAHIRA TAHIRA introduce him and his work on Wilmington’s Alice Dunbar Nelson during a black storytelling breakout session.

Ask Serena Joy — a Wilmington poet, rapper and storyteller — to tell you a story, and she starts with a little girl and a dandelion.

The little girl loves dandelions partly because she likes blowing the tiny flowers off the stem. She joyously takes some to her grandmother, who shoos her and the flower away.

“That’s a weed,” she tells her. “I don’t want them in my garden. They’ll spread everywhere.”

The lesson is learned when a boy who likes the girl brings her a bouquet of dandelions, she dismisses the gift and gesture.

“Those are weeds,” she tells him.

Yet, says Joy, there are several definitions of weeds.

One is that it’s an unwanted plant. One is that it’s a plant that takes over a garden because it is so powerful, she said.

“Who told you we weren’t flowers?” she asks the audience. “Who told you we were weeds?”

The story refers to how she often has felt as a young Black woman making her way in the world.

“There’s so many layers to it, but the point is that we are all flower enough to grow,” she said. “Because I’m Black, sometimes people may feel like I can only go so far or I’m not beautiful enough for this world and even as a Black person, just not feeling flower enough to grow is a reality sometimes.”

Black storytelling residency

Joy was one of the dozens of master storytellers taking part in the city of Wilmington’s first Black Storytelling residency. The program, modeled on the city’s decades-old Boysie Lowery Jazz Residency, brings talented professionals to town for a week-long intensive study of storytelling, stories themselves, and the history makers of Wilmington and Delaware.

The idea for the residency came from Johnathan Whitney of Flux Creative Consulting. He suggested it to Tina Betz, executive director of Cultural Affairs and Fund Development for the City of Wilmington, when they were talking about programming for the new amphitheater to be named for Lowery, a beloved Wilmington music teacher.

Whitney wanted to include a storyteller and … boom chicka boom, don’t cha just love it … the mental connection was made.

Whitney called TAHIRA TAHIRA (whose legal name is repetitive and capitalized). She runs TAHIRA Productions, a performing arts organization in Claymont.

She loved the idea and suddenly, she was in charge of the Wilmington Black Storytelling Residence.

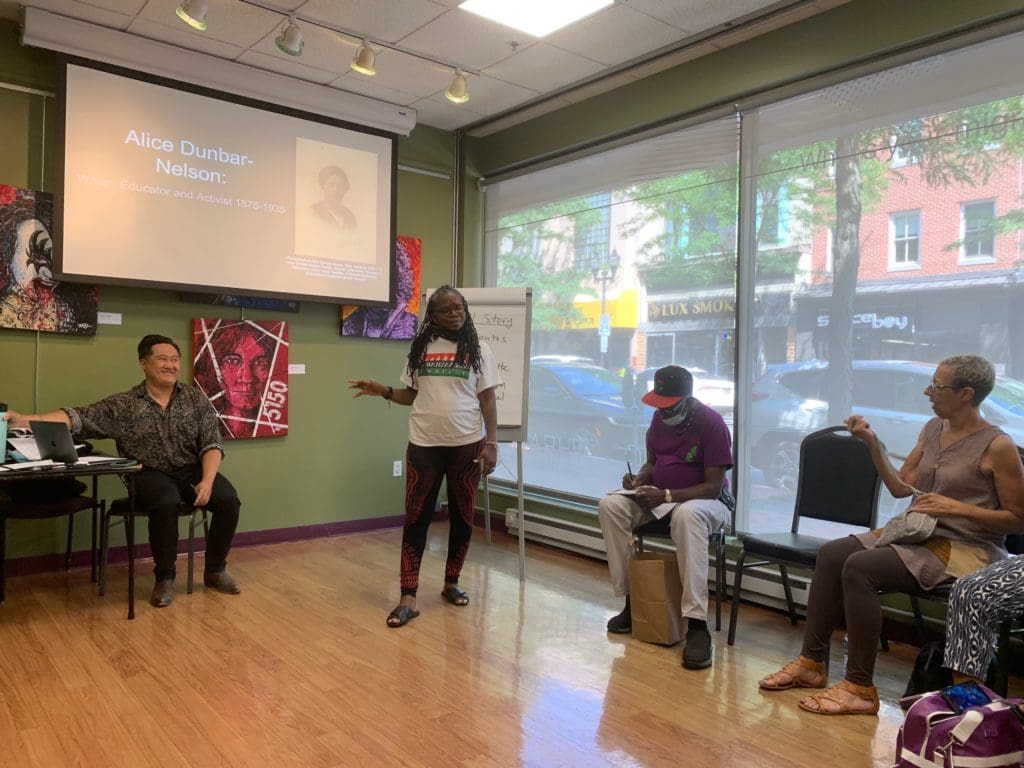

Black storytellers gather in the Ed Loper Sr. gallery at the Christina Cultural Arts Center to hear a speaker.

To participate, storytellers had to send in resumes and tapes of their performances. Many of the attendees are members of their own state or national storytelling groups and many sit on state and urban government arts committees.

The point of the residence wasn’t just storytelling, the participants made clear.

It is Blackstorytelling — one word, a form that connects the speaker to her or his roots, that honors those who have gone before in their journey interrupted by slavery, and that speaks truth to today’s listeners.

“Blackstorytelling is a tool of joy, a tool of resistance, a tool of preserving history or perpetuating traditions and culture,” TAHIRA said. “And that art form itself is powerful.”

Bunjo Butler of Baltimore, a librarian and member of the National Association of Black Storytellers, said the art form is an extension of the communal nature of the African diaspora.

“We share in the African oral tradition, we share out of our culture, we share from our life experiences being black, and especially being black in the United States,” Butler said.

“But our purpose comes from the African diaspora. We learn from the African diaspora that we are another gentleman generation that shares in that manner. And each of us because we are another generation and we are different ages have a perspective that our voice enables us to share with one another.”

Butler was one of the few men who applied for the residency. TAHIRA says she’s still trying to unpack that because most other storytelling forms are dominated by males and often white males.

Hallmarks of Black storytelling

TAHIRA pointed out that Dr. Caroliese Frink Reed of Philadelphia, the main master storyteller leading sessions this week, told them a distinction between black storytelling and other storytelling traditions is that it was and is continually being forged, honed, shaped by the conditions of oppression and the resistance to oppression that brought it forth.

“It is unbroken connection to the Negritude Movement, the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, tales on a plantation, songs sung on ships,” Reed wrote. “Black storytelling holds its place and position and a legacy of black expressiveness. That’s the difference between black storytelling and other storytelling traditions.”

The words and expressions used in the stories themselves are often far more colloquial than formal English tales.

One, pointed out by Cynthia Battle of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is the transition “hold time” used in black storytelling. It indicates to a listener that the speaker is jumping to another time period.

Some people would call it ebonics, she said.

“But you think about (Black poet) Paul Laurence Dunbar, how he was able to turn language into a beautiful symphony,” she said. “I think that more than ever before, storytelling needs to be exposed, because it shows the appreciation of the trials and tribulations that we survived and went through, and we’re still here and we’re special. We have a message to share with our future generations.”

Joy noted that storytelling also reflects changing language. She pointed to expressions used on Instagram and other social media and how they invade everyday language.

The Black storytelling tradition also demands that the teller give credit to those before them, partly to acknowledge the legacy.

But today’s storytellers also can restore credit.

Gwendolyn J. Napier, known in Atlanta as storyteller Miss LuvDrop, often appears at the Wren’s Nest, the Georgia home of Joel Chandler Harris, famed for his Brer Rabbit and Uncle Remus stories.

“You’ve got to know how to tweak the stories of Brer Rabbit,” she said. “We tell the story and we tell the stories in the correct way, and we make sure that we let everyone know that George Terrell is the original person who told those stories, and not Joel Chandler Harris.”

The Brer Rabbit stories include a lot of animal tales from Africa, and Harris is said to have heard those stories from Terrell, a former slave, before writing the books, which were a national sensation.

Battle said she came to the residency as a storyteller.

“Now I’m a Black proud storyteller, because I will demand the respect of sharing a story,” she said.

“You just can’t call me and say I want you to do a story. I need to know what kind of story it is. This is what I’m going to bring. These are the ancestors and experiences that I’m working with.”

Betsy Price is a Wilmington freelance writer who has 40 years of experience.

Share this Post